What does a pre-Hispanic altar look like? Since when has Día de los Muertos been celebrated? There are many questions surrounding this Mexican tradition.

On Google, users often search for various topics, and some of these queries are related to how Día de los Muertos was celebrated during the pre-Hispanic era.

Regarding this tradition, here’s some useful information:

What were altars like in the pre-Hispanic era?

The first thing to note is that Día de los Muertos as we know it today is a tradition that emerged from the blending of indigenous death rites and Catholicism.

The modern celebration is NOT 100% indigenous. In other words, the ancient Mexicans did NOT celebrate Día de los Muertos as we know it today, nor did they set up altars waiting for their deceased loved ones to return.

However, the current celebration does incorporate some elements from the festivities of ancient Mexicans.

How was Día de los Muertos celebrated in pre-Hispanic times? The Mictlan

The Mexicas were the dominant culture in Mesoamerica when the Spanish arrived. For them, death was the beginning of a journey to a place called Mictlán, the underworld or realm of the dead.

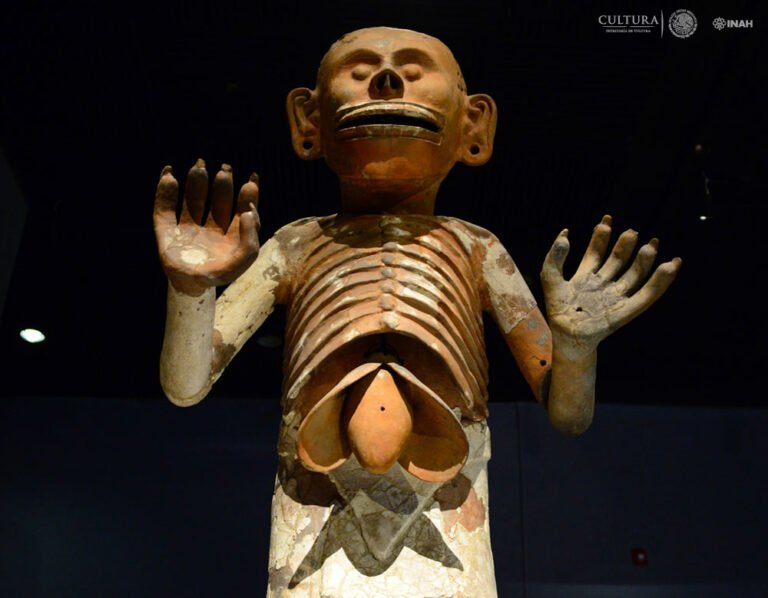

Before reaching Mictlán, the soul had to detach from the body. Tlaltecuhtli, the Earth goddess, was believed to devour corpses; according to Aztec mythology, after consuming the bodies, this deity would give birth to the souls, allowing them to begin their journey to Mictlán. (At the Templo Mayor Museum, you can see a monolith representing this goddess.)

The souls of the deceased traveled for four days to reach Mictlan, where they encountered Mictlantecuhtli, the lord of the dead, and his consort, Mictecacihuatl.

What are the nine levels of Mictlan?

Once they arrived at Mictlan, the souls were sent to one of nine regions, where they underwent a four-year trial period before reaching their eternal resting place, known as the “obsidian of the dead.”

The soul’s destination was determined by the type of death:

- Those who drowned went to Tlalocan, the paradise of Tlaloc.

- Deceased children went to a place called Chichihuacuauhco, where a tree dripped milk from its branches so they wouldn’t go hungry.

- Mictlán was reserved for those who died of natural causes.

The most desired death for ancient Mexicans was in battle or sacrifice, as those who died this way went to Omeyocan, the paradise of the Sun. After four years, they returned to life as hummingbirds. This privileged afterlife also applied to women who died in childbirth.

What does a pre-Hispanic altar include? Characteristics

For ancient Mexicans, offerings were not part of a special date following someone’s death, as they are today. Instead, they were closely tied to funeral rites and were part of the burial itself.

The bodies of the deceased were buried along with a series of items considered essential for their journey to Mictlán, the underworld. These included jewelry, clothing, and vessels containing food and water, all carefully placed in the tomb. Additionally, ancient Mexicans believed that dogs played a special role as guides in the afterlife, so they were also buried alongside the deceased.

For rulers and people of the upper classes, burials were even more elaborate. In addition to dogs, they were buried with their slaves, who were expected to serve them in the afterlife. This reflected the belief in the continuation of social hierarchy beyond death.

When was Día de los Muertos in pre-Hispanic times?

The celebration of Día de los Muertos on November 1 and 2 is a Catholic tradition, as ancient Mexicans had different dates for honoring the dead.

- Miccailhuitontli was a celebration dedicated to deceased children and took place in August.

- Hueymiccailhuitl, held in September, was considered the great feast of the dead. Both celebrations lasted 20 days.

Death was so important to the Mexicas that one day in their calendar was named Miquiztli, meaning death. It was even believed that if a child was born on this day, it was a sign of good fortune, though sacrifices of quail were required in their honor.

ALSO READ. ¿Cómo se dice pan de muerto en inglés? Esto dice el diccionario

Who invented the altar for Día de los Muertos?

The answer to this question isn’t straightforward. The origin of this tradition comes from several factors, but historian and INAH researcher Elsa Malvido conducted extensive research on the roots of this celebration.

Through her anthropological investigation, Elsa Malvido highlighted that the festivities of All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day originated in 10th-century France, created by the Abbot of Cluny.

“Continuing to think that Día de los Muertos has a pre-Hispanic origin shows we haven’t understood it. It is deeply Roman.”

“The celebrations of All Saints and All Souls have been observed in the Catholic world, but Mexican intellectuals turned them into Mexica and pre-Hispanic traditions, and anthropologists believed it.”

It was during the administration of Lázaro Cárdenas that the “Mexican identity” became associated with the most developed pre-Hispanic group at the time of the conquistadors’ arrival—the Mexicas. As a result, ceremonies were attributed to them that ignored 300 years of Spanish colonization, a century of independence, and ten more years of revolution.