The latest dispute between the United States, Mexico, and Canada over the fentanyl crisis has shaken the foundations of trade and political relations in North America. President Donald Trump threatened to impose 25% tariffs on Mexico and Canada, accusing both nations of the opioid consumption crisis affecting the United States. But the reality is much more complex.

The opioid consumption epidemic led to a severe crisis with fentanyl, but a little-known chapter of its origin lies in the unethical use of a marketing campaign. By combining multiple factors—from pharmaceutical interests to the growing demand for opioids—this has become one of the most serious public health problems for Americans.

This phenomenon places the responsibility of large pharmaceutical companies, ethics in medical marketing, and the implications of the aggressive commercialization of opioid painkillers such as OxyContin, developed by Purdue Pharma, at the center of the discussion.

How severe is the fentanyl crisis in the United States?

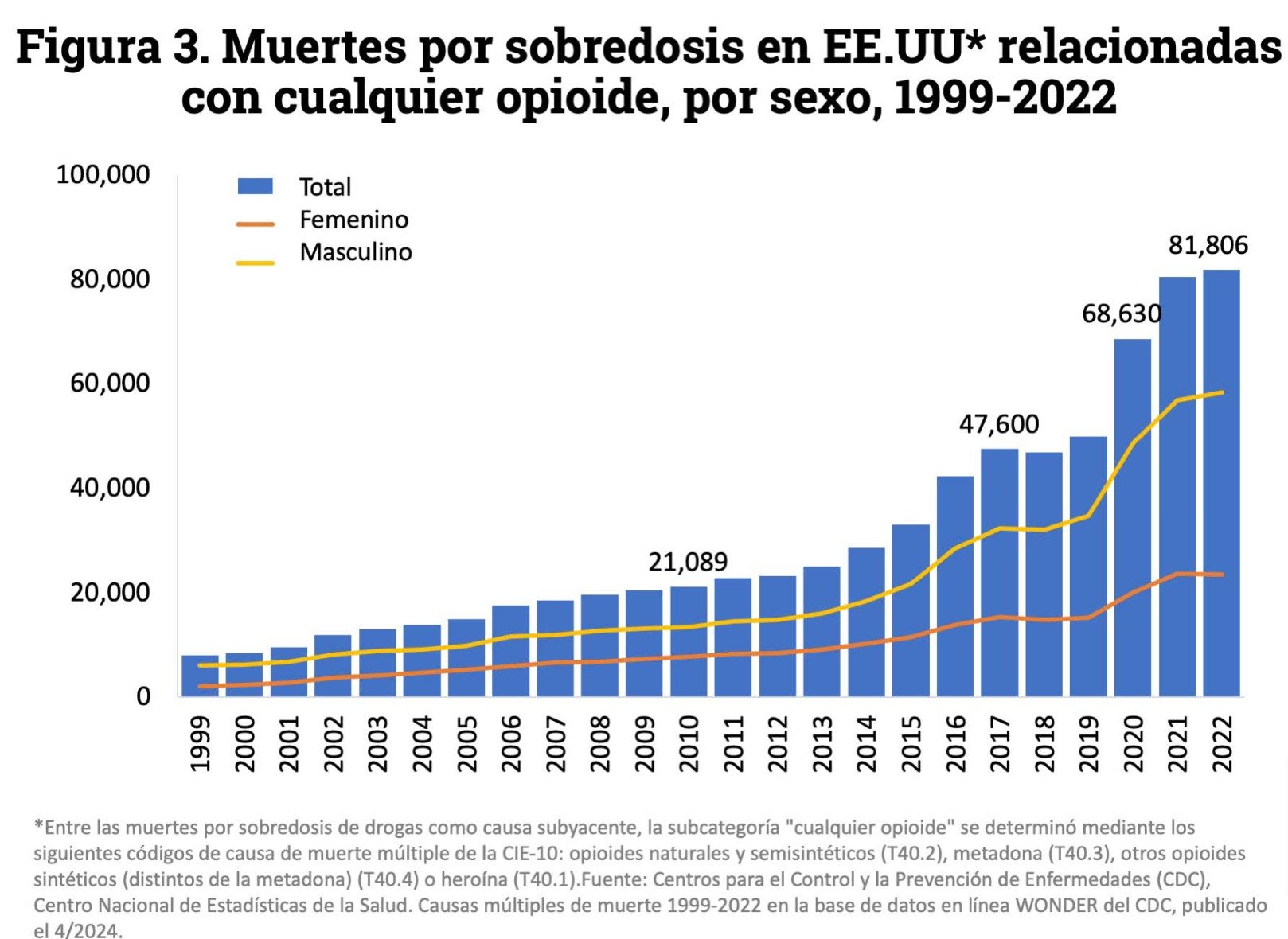

The term “fentanyl epidemic” is not an exaggeration. According to federal authorities, the opioid crisis has caused more than 500,000 overdose deaths in the United States over the past two decades. Today, fentanyl—a synthetic opioid up to 50 times more potent than heroin—has become the leading cause of fatal overdoses. Its potency and relatively low cost have made it popular in the illicit market, exacerbating the public health crisis.

Opioid consumption in the United States has increased alarmingly in recent years, with devastating consequences. According to data from the Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP), in 2021, there were 80,411 opioid overdose deaths; fentanyl, an extremely potent synthetic opioid, was responsible for 70,601 of these deaths that year.

READ ALSO. Trump’s tariffs on Mexico and Canada, explained in 10 key facts for marketers

The economic impact of the opioid epidemic is significant. The ONDCP reported that in 2023, federal drug control spending reached $44.2 billion, with a slightly higher budget request for 2025. Approximately half of this budget is allocated to substance use disorder treatment.

Despite efforts to reduce the non-medical use of prescription opioids, in 2023, an estimated 8.9 million people in the United States used them for non-medical purposes. The states most affected by opioid overdose deaths are West Virginia, Delaware, and Tennessee.

At the center of this situation is the insatiable demand for opioids in the United States and, in turn, the flow of synthetic opioids that arrive through various channels, including the border with Mexico.

The fentanyl can be synthesized in clandestine laboratories at a low cost and with relative ease of transport. In response to demands for stricter immigration and anti-drug controls, Donald Trump threatened to impose tariffs on Mexico and Canada, alleging that both nations were not doing enough to contain the arrival of this drug. Thus, the fentanyl epidemic became a matter of national security and trade tensions.

How did the fentanyl crisis start in the United States? The OxyContin case

The phenomenon did not emerge overnight; it is closely linked to the recent past of the pharmaceutical industry and its aggressive marketing of prescription opioids, which served as the main gateway to an addiction that later evolved into more potent substances like fentanyl.

To understand the roots of the current crisis, it is essential to go back to the OxyContin scandal. This painkiller, launched on the market in 1995, was presented as a “extended-release” drug based on oxycodone (an opioid) that supposedly controlled pain for 12 hours. The laboratory behind its commercialization was Purdue Pharma, controlled by the Sackler family. They were not the only ones manufacturing opioids, but they were pioneers in the mass marketing of these drugs with aggressive marketing tactics to convince doctors and patients that their use was safe and practically non-addictive.

The Sackler family and medical marketing

The history of this family dates back to the first half of the 20th century when Arthur, Mortimer, and Raymond Sackler made a fortune through medical marketing. They purchased the pharmaceutical company Purdue Pharma in the mid-century and transformed it into a profit-generating machine. During the 1960s, they also contributed to the mass dissemination of tranquilizers like Valium and Librium, in collaboration with laboratories such as Roche and with the support of advertising agencies they owned.

The strategy was clear: it relied on visits from medical representatives, paid scientific articles or academic papers with manipulated information, advertisements in prestigious magazines, bribes, and even job offers in the company for FDA officials. With these tactics, Arthur Sackler, the patriarch, laid the foundation for an unethical medical marketing approach that would later be replicated with OxyContin.

Purdue Pharma’s great contribution was not scientific; it was purely commercial. Before launching OxyContin, Purdue Pharma had achieved considerable success with MS Contin, a controlled-release morphine that allowed terminally ill patients to stay home without needing continuous hospital visits. Although it was considered an advancement in palliative care, when the patent was about to expire, the company decided to reinvent itself with a new product: a painkiller even more potent than morphine. Thus, OxyContin was born in 1993.

How unethical marketing and corruption started an epidemic that claimed half a million lives

Purdue Pharma deployed all the commercial strategy weapons learned over previous decades to promote OxyContin. The company secured regulatory approval by providing incomplete information to the FDA, bribed officials, and deceived doctors, assuring them that the risk of addiction was minimal. Purdue even struck a deal with Practice Fusion, a medical records software, to alter the algorithm so that opioid prescriptions would increase.

The truth, as revealed in internal documents, is that clinical trials showed that test subjects needed to increase their doses to alleviate pain, which triggered tolerance and greater dependence or addiction.

The aggressive advertising strategy in the sector led thousands of doctors to prescribe OxyContin even for mild or moderate pain, and “pain clinics” were created that practically distributed it without control. As a result, addiction spread, pharmacies were robbed, and networks of traffickers emerged who massively purchased prescriptions.

The outcome: more than 1,500 lawsuits were filed against Purdue, leading the company to declare bankruptcy in the United States, allowing it to halt all legal proceedings against it. Although some states secured multimillion-dollar settlements, the Sackler family did not go to jail.

In the last days of January, the Attorney General of Virginia announced a $7.4 billion settlement with the manufacturer of OxyContin for “fueling” the opioid crisis.

The history of the opioid crisis shows that the way a drug is marketed is almost as important as the drug itself. Purdue and other companies exaggerated the benefits of opioids and downplayed their addictive potential. They developed aggressive marketing strategies that included forming “alliances” with medical organizations and manipulating scientific research.

How did the opioid crisis extend to fentanyl?

The opioid crisis in the United States, initially driven by the explosion of prescriptions for drugs like OxyContin, led to a large number of addicted individuals who, unable to afford their doses or facing increasing restrictions, began to seek alternatives. It was then that fentanyl emerged as an illegal substitute, synthesized in clandestine laboratories outside U.S. territory.

Its extreme potency (it can be dozens of times stronger than heroin) and its low cost of production and transportation made it the preferred drug for cartels and traffickers.

The black market expanded, causing a surge in overdose deaths. This is how the situation evolved into the current “fentanyl epidemic” with a significant cross-border component: while demand comes from the United States, production and trafficking largely pass through Mexico.

And it is within this demand that Mexican cartels, primarily the Sinaloa Cartel, have found a highly lucrative business in fentanyl trafficking.

How much does fentanyl cost?

Fentanyl is the most profitable drug for criminal organizations. According to military intelligence data available in the Mexican Army’s database (formerly SEDENA), which was hacked by the Guacamaya group, fentanyl yields exponentially higher profits compared to other substances.

For each kilogram of fentanyl pills, which takes only a few hours to produce, profits of around $296,000 can be generated in Los Angeles, California. This sharply contrasts with the profit margins of traditional drugs like marijuana, cocaine, or heroin. While these substances can still yield significant profits (for example, heroin generates around $36,000 in the same market), they fall far short of the amounts fentanyl produces.

One of the main reasons for this enormous profit gap lies in the simplicity and speed of the fentanyl pill production process, which takes just a few hours compared to the months required for cultivating or refining substances like marijuana, cocaine, or heroin. Additionally, its increasing demand and extreme potency (dozens of times stronger than heroin) allow traffickers to sell each kilogram of fentanyl at a much higher price in high-consumption U.S. cities.

From clinics to tariffs

Trump’s stance on imposing tariffs on Mexico and Canada was based on the need to curb fentanyl production and trafficking, even though in many cases, the drug is manufactured using precursors imported from other continents.

The path that led the United States to the opioid crisis—and later to the fentanyl epidemic—is filled with complexities: aggressive marketing, regulatory loopholes, and a culture that sees medication as an automatic response to pain. From the invention of OxyContin to the White House’s pressure measures on Mexico and Canada, the story reveals how a pharmaceutical product can disrupt public health, corporate ethics, and even diplomatic relations, jeopardizing North America’s trade relationships.

What is fentanyl?

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid used in the medical field for managing acute or chronic pain, especially when patients are resistant to other analgesics like morphine. It was developed in the 1960s as a more potent and relatively fast-acting alternative. However, its potency exceeds heroin by up to 50 times and can be up to 100 times stronger than morphine, depending on the method of administration.

What is fentanyl made of?

Fentanyl, in its basic chemical composition, falls under the category of opioids. This family of substances includes everything from morphine and heroin to the latest generation of synthetic medications. How is fentanyl made? Technically, it is derived from modifying compounds that act on opioid receptors in the nervous system, particularly in the brain. These receptors regulate pain perception and the body’s stress responses.

- Molecular composition: Fentanyl contains structural chains similar to those of other opioids but with variations that increase its affinity for brain receptors.

- Potency and purity: The issue in the illegal market lies in uncertain purity levels and adulteration. There are even more potent versions (such as carfentanil), which are used to tranquilize large animals and significantly increase toxicity.

These factors make the fentanyl crisis, as part of the current opioid epidemic, even more challenging to address, as it is not always clear whether the product sold on the streets is pure fentanyl or contains even more harmful substances.

What are the characteristics of fentanyl?

To understand its destructive potential, it is crucial to analyze the characteristics of fentanyl:

- High potency: A very small amount of fentanyl can produce a significant analgesic or euphoric effect. That is why as little as 2 mg (equivalent to a few grains of salt) can be lethal for an adult.

- Rapid action: Fentanyl is quickly absorbed and rapidly reaches opioid receptors in the brain. This results in almost immediate analgesic and sedative effects.

- Forms of presentation: In medicine, it can be found in transdermal patches, intravenous injections, or sublingual tablets. In the illegal market, it often appears as a powder, counterfeit pills that mimic prescription medications, and even mixed with other drugs.

- High overdose risk: Due to its potency, even a minimal dosing error can trigger respiratory arrest. This makes it one of the most dangerous opioids.

How is fentanyl produced?

Unlike natural drugs such as marijuana or traditional opioids like opium and heroin (which are derived from the poppy plant), fentanyl is an entirely synthetic compound.

- Controlled chemical synthesis: In legitimate pharmaceutical environments, it is produced in laboratories under strict compliance with quality and safety standards. This involves using reagents and chemical processes to create the fentanyl molecule.

- Clandestine laboratories: In the illegal market, synthesis also occurs in clandestine labs with little or no technical oversight. As a result, products vary in purity and potency, increasing the risk of overdose.

- Raw materials and precursors: The synthesis of fentanyl requires chemical precursors (often sourced from Asia) that, after several refinement steps, result in the final product.

Fentanyl symptoms: What are the signs of use?

Early detection of potential use is vital to prevent severe complications. Fentanyl symptoms can vary from person to person but commonly include:

- Euphoria and extreme relaxation: The substance induces an intense sense of well-being, similar to a heroin high, but much faster and potentially more dangerous.

- Drowsiness and dizziness: The individual may experience deep sedation, affecting their ability to stay alert.

- Mental confusion: Cognitive impairments, such as difficulty concentrating or responding coherently, are common.

- Respiratory depression: This is considered the most dangerous symptom, as it can lead to a severe reduction in breathing rate and ultimately death from overdose.

- Nausea or vomiting: These are common bodily reactions to excessive opioid consumption.

If you suspect someone is exhibiting these symptoms in a fentanyl (or other opioid) use context, seek immediate medical assistance. The antidote naloxone can reverse the effects of an overdose, provided it is administered promptly.